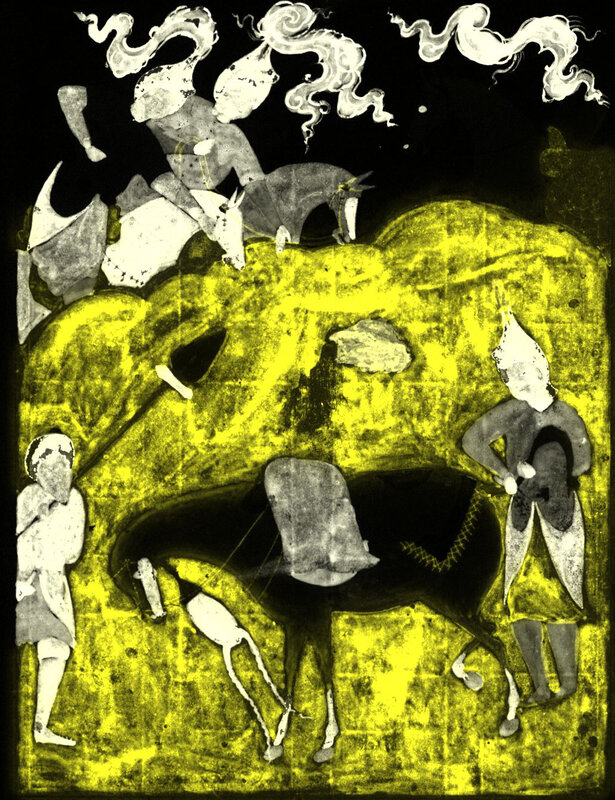

A close visual examination of this watercolor from the Shahnama, or Book of Kings, a chronicle of the rulers of greater Iran from the creation of the world to the Arab conquest in 651 C.E., revealed that the painting’s original colors had altered over time (fig. 1). Gallery conservators worked with conservation scientists at Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH) to look deeper into the painting’s support and pigments in order to treat the discoloration.

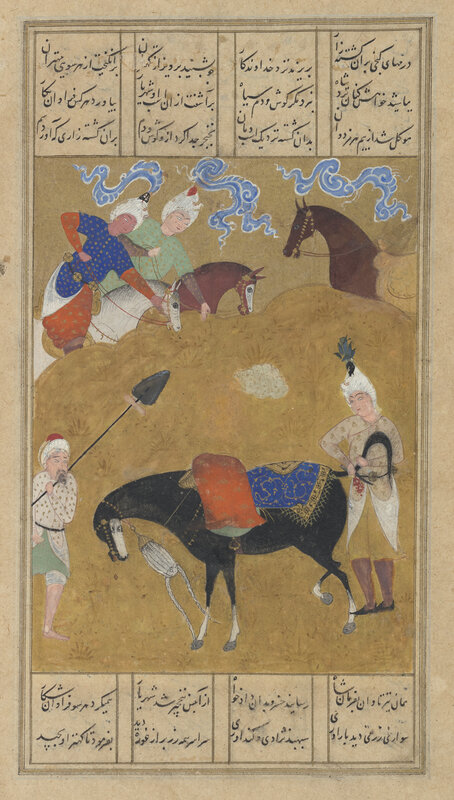

Produced in southern Iran by an unknown artist and calligrapher, the manuscript dates from the Safavid period in the 16th century. Abu’l Qasim Firdausi authored the text in the 11th century, collecting Iranian stories and setting them to verse—more than 50,000 rhyming couplets in all, amounting to the longest poem ever written by a single author. With a blend of history and lore, the Shahnama presented models of leadership and conduct that guided generations of rulers.

This miniature depicts a court official cutting the tail of Prince Khusrau Parwiz’s horse, the prince’s punishment for letting his horse escape its stall and eat some of a local farmer’s crops. Since the prince’s father had just declared harsh penalties for unruly behavior, the depicted scene of the son’s punishment speaks to his fair leadership. The disgruntled farmer, visible to the left, watches closely to see this carried out, while two court officials stand by on horseback beyond the hill. Some areas of the painting remain unfinished, including the hill and two of the saddles.