September 14–January 27, 2019

Works on view attest to the enduring appeal and impact of visual humor

Seriously Funny: Caricature through the Centuries celebrates the Yale University Art Gallery’s recent acquisition of several important 19th-century French caricatures and satirical prints. In the second quarter of the 19th century, well-known artists in France such as Honoré Daumier, J. J. Grandville, and Charles-Joseph Traviès crafted compositions that humorously responded to the political climate, social mores, and fashions of their day. These riotous prints lampooned their audiences’ foibles and famously tested limits with their visual commentary on France’s monarchy and government. As artists and publishers capitalized on the relatively new lithographic process—and the ability to quickly produce an abundance of impressions that could be rushed to a ready market—the popularity of these caricatures turned lithography from a once-fledgling medium into a flourishing one.

Seriously Funny aims to contextualize these French lithographs within the larger comedic graphic tradition in Europe and America by installing them alongside prints, drawings, paintings, and sculpture from the 16th to the 21st century. The 35 works on view are drawn largely from the Gallery’s collection with several exceptional loans from the Yale Center for British Art and private collections. With its jocularity often mistaken for triviality, caricature has long been misunderstood as inferior to artworks created in the classical Grand Manner, the large and imposing academic easel paintings that artists were trained to emulate. Though caricature may lack the refinement and lofty messages of so-called high art, its unique objectives and ambitions imbue the genre with its own power.

In its earliest incarnation, caricature was not wholly separate from high art; rather, both were products of the artist’s studio. Whereas painters and their apprentices aspired to create idealized portraits, landscapes, and religious and historic scenes, the practice of exaggerating physical features for a caricature proved to be a crucial exercise in imagination and artistic license. As caricature evolved as a genre, though, it progressed beyond the mere exaggeration of facial and bodily features. Just as Titian and Guercino—the creators of two of the earliest caricatures in the exhibition—manipulated the perfect bodies that had been a staple of their serious-minded repertoire as painters, soon other artists upended the heroic and moral subjects of Grand Manner art, creating decidedly more unconventional compositions that ridiculed human limitations, odious interests, and ill manners.

In the late 17th century, some artists moved past the more general derision of social types and customs toward the production of personal caricatures that were directed at specific individuals. Popularized by the Italian painter and caricaturist Pier Leone Ghezzi in the 18th century, these parodies spotlighted singular targets who were seldom offended, as the taunting nature of caricatures during this period never rose above gentle ribbing. While physiognomic distortion abounded in individualized caricatures, it was these exaggerated features that were believed to capture a person’s character and that permitted viewers to readily recognize the subject. Some individuals even commissioned caricatures of themselves to bolster their own renown or social standing. Similarly, artists drew and exchanged caricatures among themselves, as both a mark of camaraderie and a way to acknowledge the shared experience of their community. To this day, the principles of notoriety and recognition—and the delicate balance between the two—continue to serve as the foundation for caricature, whether the images are personal, social, or political in nature.

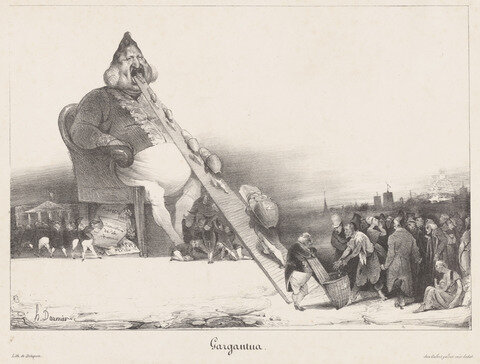

By the 19th century, the audience for caricatures had broadened significantly—as had the distance between artists and their subjects—and caricatures of famous figures, such as royals and politicians, proliferated. Personal and political caricature collide in Honoré Daumier’s Gargantua (1831), a highlight of the exhibition. In this print, which is titled after a folkloric giant who was the subject of a series of eponymous novels written by François Rabelais in the 16th century, Daumier satirized the French king Louis-Philippe I, who is seated on a chaise percée (commode) while his ministers continuously feed him moneybags of taxes collected from nearby impoverished citizens. Another cluster of ministers rushes out of the legislative building in the background to greedily collect the by-products of Louis-Philippe’s “digestion”: prefectures, nominations of peers, and military commissions for his supporters. Audiences both past and present can find amusement in Gargantua, which drew connections between Rabelais’s willful giant and the 19th-century French king. Yet the 21st-century viewer, accustomed to heightened political debate and daily editorial cartoons, may not grasp the incendiary and disruptive nature of Daumier’s caricature. Charged with arousing contempt for the government and offending the king’s person, Daumier was fined and imprisoned for creating the print.

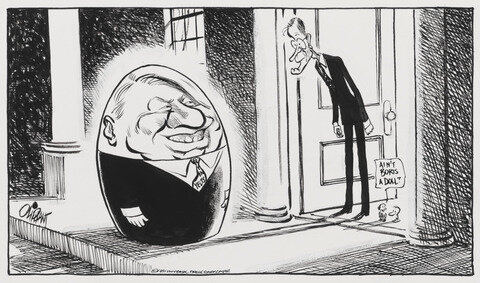

Daumier paved the way for satirical artists today, such as Enrique Chagoya and political cartoonist Pat Oliphant, who continue to push boundaries by voicing dissent and questioning accountability. Caricature remains an effective and vital vehicle for engaging with subjects that are familiar and accessible, yet difficult to broach.

Elisabeth Hodermarsky, Acting Head and the Sutphin Family Senior Associate Curator of Prints and Drawings, states, “The works in Seriously Funny are both pointed in their purpose and masterful in their execution. Caricature is a unique and challenging genre requiring extraordinary draftsmanship, dexterity of mind, and compositional genius. Visitors can appreciate both moments of profound wit and sublime artistry in this exhibition.”

Rebecca Szantyr, exhibition curator and the former Florence B. Selden Senior Fellow in the Department of Prints and Drawings, explains, “When these works were created, they were—by definition of what the genre does best—very much ‘of the moment,’ be it encapsulating the characterization of an individual, parodying a social scene, or commenting on a political current event.” Szantyr continues, “Yet, it would be a mistake to understand this as a mere topicality, or to think that, because these works are comical, they are therefore less prestigious. In the objects presented, viewers will find not only that the humor at work in them transcends traditional temporal boundaries but also that this humor is a conduit for addressing issues of great consequence.”

On View

September 14–January 27, 2019

Related Programs

Gallery Talk

Wednesday, October 24, 12:30 pm

“The Medium Is the Message: Printmaking Technology and Audience”

Rebecca Szantyr

Lecture

Friday, October 26, 1:30 pm

“What’s So Funny?”

David Sipress, staff cartoonist for the New Yorker

Studio Program

Friday, November 9, 1:30 pm

“Seriously Funny: Political Cartoons from All Sides”

Rebecca Szantyr and Anna Russell

All programs are free and open to the public unless otherwise noted. For more detailed programming information, visit artgallery.yale.edu/calendar.

Exhibition Credits

Made possible by the Wolfe Family Exhibition and Publication Fund. Exhibition organized by Rebecca Szantyr, the former Florence B. Selden Senior Fellow, Department of Prints and Drawings.