Card Players by the American artist and educator Hale Woodruff (1900–1980) is an important recent addition to the Yale University Art Gallery’s collection (fig. 1). During the Gallery’s closure due to the pandemic, the painting received treatment for minor condition issues in the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH) Conservation Lab. Conservators examined the artwork with close looking, microscopy, technical imaging including ultraviolet fluorescence photography, X-ray fluorescence mapping (MA-XRF), and portable Raman spectroscopy, which together revealed many fascinating aspects of the artist’s materials and creative process.

Technical Examination of Hale Woodruff's Card Players

fig. 1: Pre-treatment image of Hale Woodruff’s 1958 Card Players. © Hale Woodruff/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The 1958 oil painting on canvas is the second in a series of three renditions of the same subject that Woodruff created over the course of his career. The 1930 Card Players is held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the 1978 work is in the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture, Charlotte, North Carolina. Woodruff’s early career took him from Nashville and Indianapolis to Paris and beyond. While in Atlanta during the 1930s and 1940s, he created depictions of life in the American South, helped establish an art degree program at Atlanta University, and worked to provide new exhibition opportunities for Black artists. Woodruff spent the latter part of his life working as an artist and teacher in New York, where he co-founded the Black arts collective Spiral during the civil rights movement. It was in New York that he painted the 1958 Card Players.

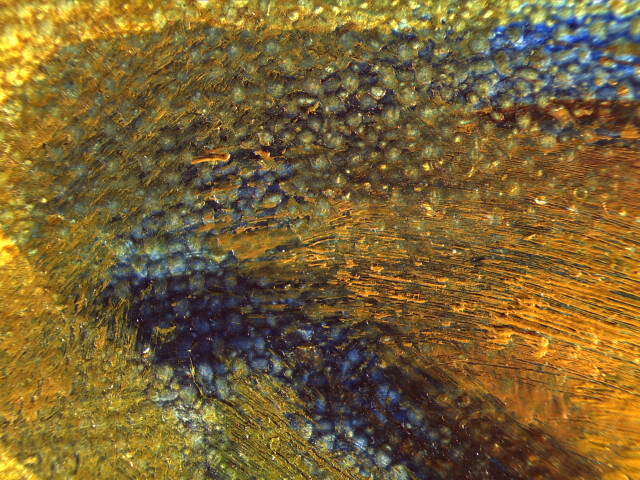

Whereas the 1978 rendition closely follows the one from 1930, the Gallery’s painting shows Woodruff rethinking elements of his earlier composition: the positions of the plant, side table, and checkerboard are reversed; the angles of the figures are changed; and the palette is lighter in tone. The painting was executed on a commercially prepared linen canvas with a priming containing chalk (calcium carbonate) and titanium white, a common support for 20th-century painters. The artist did not use extensive underdrawing nor did he meticulously copy or trace the 1930 arrangement. Instead, he started by loosely sketching out the composition on the primed canvas mainly using dilute blue paint. The placement of some of these marks indicates that Woodruff might have initially been planning a composition closer to that of his 1930 and 1978 canvases. For example, lines of underpaint forming a triangular shape to the right of the chair may show the originally intended placement of the side table, corresponding to the other two paintings. Some of the underpainting was so fluid that the paint ran down the canvas. Drips can be seen not only through the paint layers but also along the bottom tacking margin that holds the canvas to the stretcher and is not visible from the front, which means that Woodruff painted the canvas before stretching it. Around and over the painted sketch he applied color in energetic strokes, sometimes reinforcing the underpainted lines. In other areas, he formed some of the final outlines of his composition by leaving the blue underpaint visible, as evident in a photomicrograph of one of the sitters’ eyes (fig. 2).

fig. 2: Photomicrograph of the eye of one of the sitters, showing how Woodruff’s initial blue sketch functions as an outline

By layering thin and often semitransparent colors on top of one another, Woodruff created nuanced tonal shifts. To visualize the use of pigments and their application across the painting, IPCH conservation scientist Marcie Wiggins carried out MA-XRF, an analytical technique that scans an artwork and generates a map of the distribution of inorganic elements, from which pigments can be inferred. A map of Card Players registered the calcium signal from the chalk in the priming in the areas where the paint is thinnest, emphasizing the quality of Woodruff’s brushwork (fig. 3). The broad and thin application of paint evident here differs significantly from the smaller brushstrokes of impasto Woodruff used to convey form in the 1930 painting. Compositional alterations the artist made at the painting stage, such as the angle of the checkerboard, are visible to the naked eye yet become clearer with the aid of MA-XRF. Elsewhere—for instance, in the plants at the top left of the canvas—Woodruff deliberately left visible multiple outlines. The artist was not concerned with completely covering previous marks but seems to have appreciated the dynamism these layers imparted to the surface. Throughout his career, Woodruff admired the work of Paul Cézanne; in Card Players, the influence of Cézanne is evident in the subject matter as well as in the visible indications of the artist’s process and revisions to the painting.

fig. 3: MA-XRF map for calcium makes evident Woodruff’s application of paint in thin and energetic brushstrokes on the priming

fig. 4: Detail photograph taken during aqueous surface cleaning; the top half of the area shown has undergone cleaning, while the bottom half has not yet been treated

Using Raman spectroscopy, a laser technology that produces spectra that can be used to characterize certain materials present in an artwork, the warm blue of many of the outlines was identified as synthetic ultramarine. The painting also contains another blue called phthalocyanine, a synthetic modern pigment that came on the market in the 1930s and was thus not yet available when Woodruff painted his first Card Players. Speaking to the artist’s sensibility and skilled handling of color, this highly pigmented, transparent blue lends itself to application in the kind of thin glazes seen in the shirt of the figure on the left or in vibrant pops of color, as in the details of the card suits.

Typically, conservators use ultraviolet illumination to look at the top surface layers of a painting, which are often coated in varnish. Varnish evenly saturates the surface of a painting, providing an overall glossy finish and masking subtle nuances. Woodruff, however—like many artists of the 20th century—embraced these inconsistencies in the painted surface by not using varnish, as revealed by ultraviolet examination of Card Players. Cleaning the painting with a gentle aqueous solution removed dirt that had gathered on the surface over time and restored variations in gloss and clarity in color (fig. 4).

Methods of technical imaging and scientific analysis can deepen our understanding of how and with what materials an artwork was made. As with MA-XRF and Raman spectroscopy, these analytical techniques are often noninvasive. The knowledge gained from these can add to our experience of an artwork but cannot replace the joy of spending time with it, observing and enjoying the artist’s creation. Woodruff’s inspiring painting is now on view, and I invite you to visit the Gallery and take a look.

Anna Vesaluoma

Postgraduate Associate in Paintings Conservation

Related Content

-

Conservation: Selected Websites

Resources like ours help individuals and institutions preserve and protect their collections.

-

Modern and Contemporary Art

The modern and contemporary art collection is noteworthy for exemplary works from the 20th century and the early years of the 21st century.